By Paul Guirguis and Susan Ross

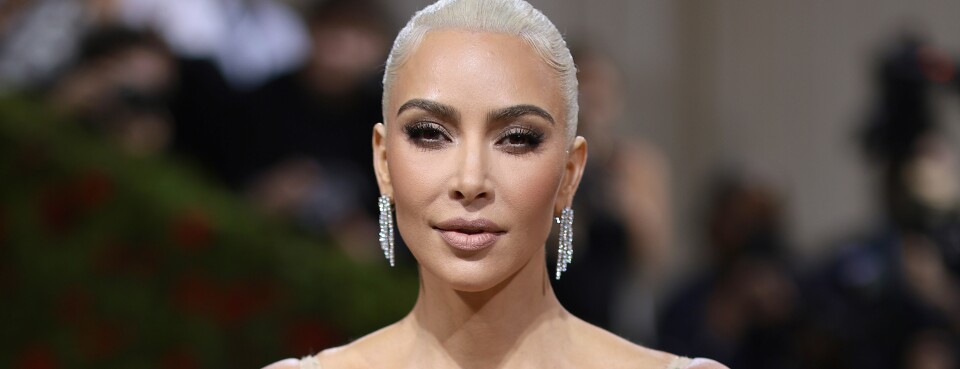

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s recent $1.26 million settlement with Kim Kardashian holds lessons for other influencers and their attorneys, say Norton Rose Fulbright’s Susan Ross and Paul Guirguis. They lay out SEC and FTC rules and guidance governing celebrity endorsements of cryptocurrency and other digital currency assets.

In speeches, studies, and reports, regulators around the world have continued to signal that they are watching cryptocurrency assets and social media influencers. A recent settlement between the Securities and Exchange Commission and Kim Kardashian highlights more enforcement actions could be on the horizon.

The settlement should be taken as a warning to social media influencers and their attorneys.

Based on their specific design, some crypto assets meet the definition of a security and some do not. Celebrity endorsements of crypto assets typically require a disclosure that the celebrities are being paid to make the endorsements.

Crypto assets that meet the definition of a security require additional important disclosures and considerations regarding risks and suitability for individual investors when advertised.

In a recent case where the defendants tried to shield themselves from liability under the Security Act for their online videos and social media posts, the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reversed the lower court’s decision to grant a motion to dismiss and remanded the case for further proceedings.

The appeals court firmly found that those communications were the equivalent of their mass communication predecessors, such as newspapers and radio advertisements. Therefore, those who promote securities on social media are potentially liable under Section 12 of the Securities Act.

First and foremost, creators and marketers must understand whether the crypto asset being promoted might be considered a security, and should be very cautious if the answer is even “maybe.”

There are some additional issues to consider that might be red flags for regulators and plaintiffs.

Suitability and Disclosures: Avoid mass-marketing a crypto asset that might be considered a security. In addition to disclosing endorsements and existing positions, marketers should understand the potential civil and criminal liability of mass-marketing a security. There is no way to determine the suitability of a crypto asset for an individual investor if it is being mass-marketed.

Targeted Ads: Directly related to determining suitability and providing appropriate disclosures, outsourcing advertising, or trusting posts to be disseminated by algorithms written by third-party marketing agencies expose companies and influencers to the risk that those posts will be put in front of someone not suitable for that specific security.

Crypto Asset Naming: Consider whether or not the security being created and marketed might create confusion with other established products.

Fear of Missing Out and Extreme Pricing: Be cautious with extremely priced, that is, very cheap crypto assets. When celebrities and influencers post about crypto assets they inevitably create a fear of missing out.

Extreme pricing of certain crypto assets further fuels this fear. For example, when an asset is priced to the one-one millionth of a penny, it is easier to daydream about the astronomical real dollar returns that in reality would seem unrealistic or impossible if that same asset was priced at one penny.

A stock priced at one penny would have to rise to $1,000,000 per share for it to have the same return as an asset priced at one-one millionth of a penny rising to just one dollar.

It’s hard to imagine a security having a price per share that comes anywhere near $1,000,000, but it’s easy to dream of that one-dollar security continuing to grow to $100 or $1,000. Furthermore, such extremely priced crypto assets are potentially more vulnerable to market manipulation, and could be used by fraudsters to generate greater returns.

The days of the unregulated crypto asset, whether as a security or a commodity, are coming to an end. Prudence is recommended when creating and marketing crypto assets, because regulators are not just watching these markets, they are bringing enforcement actions.

The Federal Trade Commission’s Endorsement Guides (not formal regulations), originally issued in 1980, simply require a disclosure of a “material connection” that might affect the weight or credibility that consumers give the endorsement.

In 2019, the FTC issued guidance specifically aimed at social media influencers. The agency offered the guidance in the context of social media and celebrity endorsements.

The following terms and hashtags—used to identify or organize topics in social media—are ambiguous and should not be considered adequate as the disclosure of the material connection: “Thanks” #collab #sp #spon #ambassador.

The FTC says, “Don’t rely on disclosures that people will see only if they click ‘more.’” A hyperlink labeled “Disclosure” or “Legal” in a post “isn’t likely to be sufficient. It does not convey the importance, nature, and relevance of the information to which it leads …”

Placement of the hashtag matters. Don’t simply append “ad” to the end of a hashtag with your company name because there is “a good chance that consumers won’t notice and understand the significance of the word ‘ad’ at the end of a hashtag.”

The FTC’s Endorsement Guides simply require a disclosure of a “material connection” between the endorser and the company or product. Violations of the guides can lead to a civil action by the FTC for violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act. These actions typically result in consent agreements where the defendants agree to injunctions and ongoing audits for 10 or 20 years.

By contrast, the SEC mandates disclosure of the “nature, scope, and amount of compensation” relating to the endorsement. Unlike the FTC, the SEC has both civil and criminal authority.

Companies that wish to engage “influencers” or celebrities for promotion purposes should incorporate compliance with federal FTC and SEC requirements into their contracts, but also should monitor the behavior of the “influencers” relating to the company’s offerings.

Not only should you keep an eye on what the influencer is doing on the public pages or posts, but also include in your contract that you need to be a member or friend, or otherwise allowed to view all the “private” pages or messages.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

Paul Guirguis is an associate at Norton Rose Fulbright.

Sue Ross is a senior counsel at Norton Rose Fulbright US, and is a member of its FinTech team.

To read more articles log in.

Learn more about a Bloomberg Law subscription

Author

Administraroot