Advertisement

Supported by

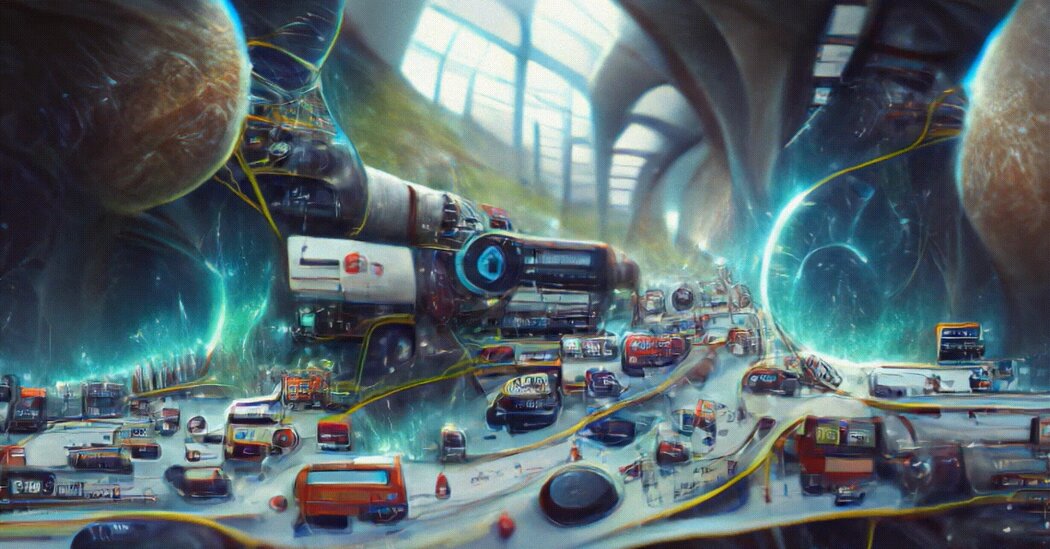

An upcoming auction by Sotheby’s is the latest attempt to recast crypto collectibles as an artistic evolution and perhaps draw interest from a wider circle of collectors.

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

When digital artworks started selling for millions of dollars last year, the shock of pixelated punks and computerized graphics turned some traditional collectors into crypto skeptics.

The argument that NFTs, or nonfungible tokens, represented the art market’s future was unappealing to the bulk of these buyers, leaving gallerists and auctioneers to focus their attention on a new class of millennial connoisseurs from the tech world.

The arrangement left auction houses prioritizing Pak cubes and Bored Apes — collectibles that are the closest one can get to brand-names in the crypto world — in sales that further alienated the skeptics.

But one year later, Sotheby’s has started using the more genteel language of art history to entice traditional collectors toward blockchain-based collectibles for a sale, Natively Digital NFT. It is running April 18-25 and is designed to unite early pioneers of computer art with their crypto counterparts.

Traditional collectors are often drawn to provenance and pedigree, so a sale focused on the lineage of computer art might help convince them that NFT artists have a stronger art historical foundation beyond the beep and boop of internet forums.

The event features some of the earliest examples of generative art, a genre where control of the creative process is determined by algorithms or a predetermined process to create images. Examples include artists working in the 1960s and 1970s like Vera Molnar, Chuck Csuri and Roman Verostko alongside more recent offerings from the digital artists Dmitri Cherniak, Tyler Hobbs and Anna Ridler.

The Sotheby’s press release says “the prescient and pioneering work” by Molnar, Csuri and Verostko “has provided the foundation for the digital artists at the forefront of the digital art and NFT movement.”

“Generative art is a movement that has sparked interest,” said Michael Bouhanna, 30, a contemporary art specialist who organized the Sotheby’s sale. Having more than a half-century of history behind generative art helps soothe the skeptics, he said, adding, “Discussions with traditional collectors have been easier.”

NFTs of art and collectibles generated more than $23 billion in sales, according to some industry reports, a number that some experts have said could indicate a bubble getting ready to burst.

The art adviser Todd Levin said that sellers are producing more historically informed exhibitions to broaden the market’s appeal and create a sustainable business model.

“These are the godfathers and godmothers of digital art that you need to know,” Levin said of the older artists included in the auction. “You can’t just keep selling NFTs without that cultural context.”

In February, an anonymous collector who had consigned 104 CryptoPunk NFTs for sale at Sotheby’s withdrew them at the 11th hour. The auction house had estimated that the CryptoPunks, popular works that are some of the earliest minted on the Ethereum blockchain, could fetch as much as $30 million — and the sale was viewed by some collectors as a measure of the NFT market. But the early bidding was lackluster and after the consignor had withdrawn his digital collectibles from the sale, he posted a meme on Twitter mocking the auction house for believing that he actually wanted to sell his NFTs with them.

Later, he used the collection as collateral for an $8.3 million loan that was registered on the blockchain by a company called NFTfi. Levin said that the exchange demonstrated that the CryptoPunks collection still had a market, but perhaps not as ravenous as the auction house had hoped.

“He could have his cake and eat it, too,” Levin said. “He gets $8 million to play around with and didn’t have to sell his CryptoPunks to raise the money.”

There are indications that the new historical approach is working. Earlier this month, Sotheby’s sold a receipt by the French artist Yves Klein for $1.2 million, nearly double its high estimate. The small piece of paper was part of the artist’s 1959 project called “Zone of Empty Space,” a project touted as the first tokenization of art, decades before NFTs became popular. The art process typically involved Klein giving buyers receipts in exchange for gold. In some cases — clearly not all — buyers burned their receipts while Klein dropped half of their payments into the Seine.

Although her name isn’t yet as recognizable as Klein, Molnar’s star is rising as collectors look for the origin story of digital art from the analogue era of the 1960s. The Hungarian artist, now 98, currently has solo exhibitions at the University of California, Irvine and the Venice Biennale. And she has embraced the digital movement, creating a new NFT for the auction, with a high estimate of $150,000 — nearly 10 times as much as the high estimate on the early work, “1% de désordre,” she is offering at auction.

“I’ve become so used to not being known, to working in my corner,” Molnar said in an interview over email about the newfound recognition she is receiving. “It feels good!”

(Molnar created her first computer drawings in 1968 by using an IBM machine and punch cards.) “I hate everything that is natural and I love the artificial,” she added, speaking of NFTs. “I’m so happy to be doing this because it is the world of today.”

Advertisement

Author

Administraroot