Before declaring independence on July 9, 2011, becoming the world’s youngest officially recognized nation-state, the Republic of South Sudan selected a flag, an anthem, and a currency. Within a week of secession, the South Sudanese pound was in circulation, featuring a portrait of the deceased revolutionary leader John Garang de Mabior. By September, the currency of neighboring Sudan was no longer deemed legal tender.

The Bank of South Sudan did not have to print banknotes, let alone pay the South African Mint to strike coins showing subjects of national pride ranging from giraffes to oil derricks. Neighboring Kenya already had years of experience running payments through a mobile banking system called M-Pesa, and the blockchain was starting to host a range of cryptocurrencies beyond bitcoin. The decision to follow tradition was political, equivalent to the choice Eritrea made in 1998, shortly after seceding from Ethiopia. Even more than a flag or anthem, a state currency broadcasts national identity.

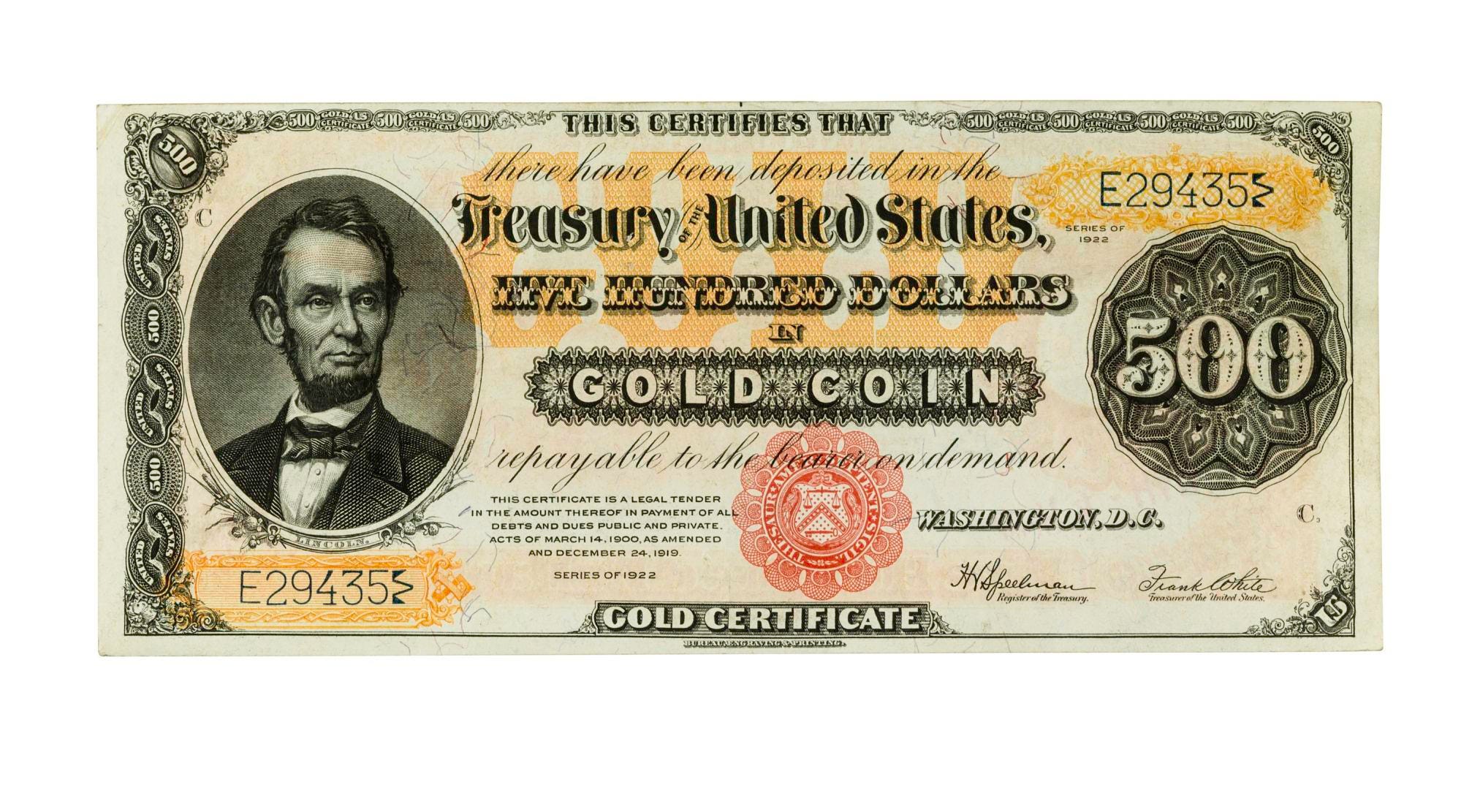

Paper money, 500 Dollar Note, 1922. Gold Certificate. Donated by U.S. Department of the Treasury. … [+]

South Sudanese and Eritrean banknotes are currently on view at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History alongside dozens of other coins and currencies from around the world and throughout history, in a permanent exhibition aptly called The Value of Money. Built on solid numismatic foundations, and expertly curated by Ellen Feingold, the exhibit only becomes more timely with each slip of the economy and freefall of cryptocurrency. Even more valuable is a new addendum opened this year for children coming of age at a time when they might never need to pocket a pound or a penny. Beneath their impressive surface luster, both exhibitions – and their comprehensive online complements – implicitly ask what money does when it isn’t merely quantifying a financial transaction.

If crypto has a premodern lineage, it might trace back to the Western Pacific island of Yap where large stones have been used in significant transactions for centuries. The stones are typically made of imported calcite, carved into a ring and set in the ground. Many are too heavy to lift, and never physically change hands. Islanders simply remembered who owns which ones, a public ledger based on shared trust.

Unlike cryptocurrencies, the Yapese rei has resisted external manipulation. A 19th century scheme by an Irish sailor to import identical stone rings by ship resulted in an increased quantity that was met with greater attention paid to when and how each rei came to the island. Stones that are older, and required greater effort to import, hold higher value: proof-of-work avant la lettre.

Rai would not be viable in a modern global economy given the complexity and number of participants. (Even on Yap, most transactions use US dollars.) Nevertheless, the rai provides valuable perspective on contemporary economics because it shows that accountability involves more than accounting. The stones have provenance. Each rai is the nonfungible product of all past transactions: a mnemonic device as much as a monetary instrument. The qualities that make rai work are anathema to crypto. More than a tech fix, a sociocultural reckoning may be needed to make cryptocurrencies stable.

Even more profoundly, technological ploys make transactions frictionless may undermine the economy. For all the manifest inconvenience of cash – and the ease of exchanging bits – the value of money needs to be understood as more than merely transactional. Throughout history, money has been a form of communication carrying multiple layers of meaning. From the ancient agora to the Mall of America, the marketplace is a forum of ideas.

Some of the earliest money was made in China, where coins were cast in the shape of tools such as spades and knives. Inherently worthless, these token objects recollected real implements with actual utility value, items that had traditionally been bartered for livestock and land. The change to a make-believe version in the 7th century BCE increased commerce by easing exchange – i.e., friction was reduced by lightning the load – but these coins reminded people at every trade that money was merely symbolic. Well represented in the Smithsonian collection, knife and spade money arguably countered the abstraction of wealth and the concomitant distortion of values.

Knife money, China, 5th-1st century BCE. Howard F. Bowker Collection. Courtesy of the National … [+]

In the Near East, money evolved independently, taking an entirely different trajectory. Around the same time that China was casting miniature tools in bronze, the kingdom of Lydia (located in modern Turkey) started striking coins in a natural alloy of silver and gold. Previously most transactions in the region had involved the exchange of bullion, which required weighing and assaying with every exchange. With the stater and its fractions – soon struck in pure gold or silver instead of alloyed electrum – Lydia standardized monetary units while also certifying authenticity.

Lydia was defeated by the Achaemenid Empire in 547 BCE. Learning metallurgy and minting from their new subjects, the Achaemenid kings started to issue their own coinage in precious metals with one signal difference: In contrast to the lions and bulls gracing Lydian staters, the new sigloi portrayed the monarch, depicting him as a kneeling archer with drawn bow. Wherever the Achaemenid currency spread, it carried an implicit threat of colonization.

Ever since, most coinage has been struck with subtexts ranging from political propaganda to visions of the future. The Value of Money includes an Athenian tetradrachm, which became the de facto currency throughout most of ancient Greece in the 4th century BCE, radiating the prestige of the city and spreading the glory of its patron deity with a spectacular portrait of a helmeted Athena. The exhibition also includes a Colonial American cent from 1786 prominently displaying the Latin motto E Pluribus Unum (“Out of Many, One”), reinforcing the call to common purpose articulated by the Founding Fathers. And a map of Europe appears on a euro coin dating from the year 2000, charting an alliance that was still in the making, suggestively seeking to connect the continent economically.

There is a risk of overstating the rhetorical power of money. This becomes especially apparent when money must stand on its own, devoid of intrinsic value. China ensured acceptance of coins and pioneered paper currency through the strength and discipline of a centralized government. For a long time, the United States and European nations imbued paper with the spirit of precious metals by solemnly guaranteeing redemption of gold notes and pounds sterling for minted bullion. But as Germany found in the early 1920s, no amount of solemnity or fancy engraving can counter mistrust of the people. In a few short years, hyperinflation added so many zeroes to the deutschmark that stacked trillion-mark notes had to be carted to market in a wheelbarrow.

Although not as extreme, inflation has also afflicted the South Sudanese pound and other newer currencies such as the Venezuelan bolivar. In the case of the latter, the Smithsonian shows how artists have used the colorful money as raw materials for origami sculptures that can be sold for considerably more than face value.

As charming as it may be, bolivar origami turns the rhetorical force of the currency against itself, undermining national dignity far more effectively than a burnt flag or an anthem sung out of key. When currency is eviscerated or trivialized by the people, the nation’s values are subject to renegotiation.

Physical qualities of money always convey meaning, whether or not it’s what the issuing authority intended. Because the meaning manifests at every transaction, each transaction is a mode of interaction. Even more than the friction that gives pause for reflection, the exchange of ideas may be the greatest value of money, and the most significant loss we might face if the world succumbs to cryptocurrency or even converts to Apple Pay.

Anything but obsolete, money is an ideal platform for social progress and economic innovation. Money can refocus national identity through the imagery portrayed. Heads were turned by the dollar coin featuring Sacagawea. The proposed $20 bill portraying Harriet Tubman promises to make an even deeper impression, given that Tubman’s visage will replace the face of Andrew Jackson.

Sacagawea coin plaster, United States, 1998. Designed and donated by Glenna Goodacre. Courtesy of … [+]

The form that money takes also has the potential to influence the terms of trade. Imagine a coin with a mirror finish, confronting the spender with a reflection of his or her facial expression. (Would it make people more honest?) Imagine a bill printed with an optical illusion that makes it appear more impressive to the recipient than to the one giving it. (Would people become more generous?) The ergonomics of money can be modulated to influence spending habits. Alloys can be altered to remember how transactions are handled.

One of the most modest coins in the Smithsonian exhibition is a slender silver denarius dating from the year 46 BCE. On the obverse is a portrait of the goddess Juno Moneta, in whose temple money was minted (and whose name is the etymological root of money). The reverse, not visible in the exhibition or on the website, shows the tools used in the minting process – tongs to remove molten metal from the furnace and a hammer to strike a design in it – effectively demystifying the process by which money comes into being. Juno may be supernatural, but making money isn’t magic.

More than two millennia after it was struck, the candor of that denarius remains unsurpassed, standing in stark contrast with the cryptic ways of crypto. In our fragile economy, the design brief for future money might begin by requesting money to explain itself. Until that happens, we’ll have to glean what we can from the numismatic galleries of the Smithsonian.

Author

Administraroot