IEEE websites place cookies on your device to give you the best user experience. By using our websites, you agree to the placement of these cookies. To learn more, read our Privacy Policy.

The project aims to scan all the world’s eyeballs

People queue up to have their irises scanned at an outdoor sign-up event for Worldcoin in Indonesia.

In a college classroom in the Indian city of Bangalore last August, Moiz Ahmed held up a volleyball-size chrome globe with a glass-covered opening at its center. Ahmed explained to the students that if they had their irises scanned with the device, known as the Orb, they would be rewarded with 25 Worldcoins, a soon-to-be released cryptocurrency. The scan, he said, was to make sure they hadn’t signed up before. That’s because Worldcoin, the company behind the project, wants to create the most widely and evenly distributed cryptocurrency ever by giving every person on the planet the same small allocation of coins.

Some listeners were enthusiastic, considering the meteoric rise in value that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin since they launched. “I found it to be a very unique opportunity,” said Diksha Rustagi. “You can probably earn a lot from Worldcoin in the future.” Others were more cautious, including a woman who goes by Chaitra R, who hung at the back of the classroom as her fellow students signed up. “I have a lot of doubts,” she said. “We would like to know how it’s going to help us.”

Those doubts may be warranted. The 5-minute pitch from Ahmed, a contractor hired to recruit users, focused on Worldcoin’s potential as a digital currency, but the project’s goals have morphed considerably since its inception. Over the past year, the company has developed a system for third parties to leverage its massive registry of “unique humans” for a host of identity-focused applications.

Worldcoin CEO Alex Blania says the company’s technology could solve one of the Web’s thorniest problems—how to prevent fake identities from distorting online activity, without compromising people’s privacy. Potential applications include tackling fake profiles on social media, distributing a global universal basic income (UBI), and empowering new forms of digital democracy.

But Worldcoin’s biometric-centered approach is facing considerable pushback. The nature of its technology and the lack of clarity about how it will be used are fueling concerns around privacy, security, and transparency. Questions are also being raised over whether Worldcoin’s products can live up to its ambitious goals.

So far, Worldcoin has signed up more than 700,000 users in some 25 countries, including Chile, France, and Kenya. In 2023 it plans to fully launch the project and hopes to scale up its user base rapidly. Many people will be watching the company during this make-or-break year to see how these events will unfold. Will Worldcoin succeed in reimagining digital identity, or will it collapse, like so many buzzy cryptocurrencies that have come before?

In early 2020, Blania started working with Worldcoin cofounders Sam Altman, former president of the legendary Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator, and Max Novendstern, who previously worked at the financial-technology company Wave. The question driving them was a simple one, Blania says. What would happen if they gave every person on the planet an equal share of a new cryptocurrency?

Their thesis was that the network effects would make the coin far more useful than previous cryptocurrencies—the more people who hold it, the easier it would be to send and receive payments with it. It could also boost financial inclusion for millions around the world without access to traditional banking, says Blania. And, if the coins increase in value (as have other cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum), that trend could help redistribute global wealth.

Most ambitiously, the founders envisaged Worldcoin as a global distribution network for UBI—a radical approach to social welfare in which every citizen receives regular cash payments to cover their basic needs. The idea has become popular in Silicon Valley as an antidote to the job-destroying effects of automation, and it has been tried out in locations including California, Finland, and Kenya. When the Worldcoin project was unveiled in October 2021, Altman told Wired that the coin could one day be used to fairly distribute the enormous profits generated by advanced artificial intelligence systems.

The founders envisaged Worldcoin as a global distribution network for universal basic income.

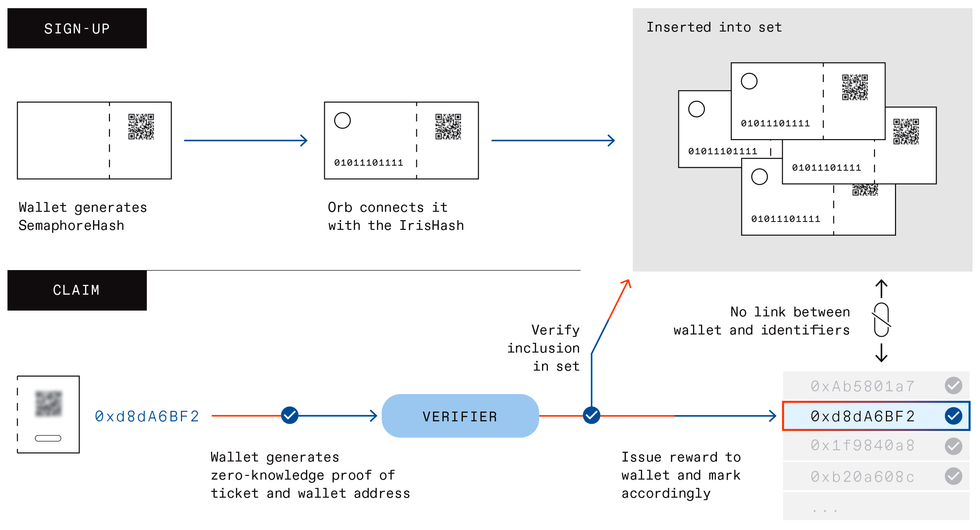

To ensure even distribution of coins, Worldcoin needed a sign-up process that guaranteed that each person could register only once. Blania says the team didn’t want to tie the cryptocurrency to government IDs due to privacy risks, and they eventually decided that only biometric iris scans could scale into the billions. Given the sensitivity of biometric data, the team knew that privacy protections had to be paramount. Their solution is a protocol based on Proof-of-Personhood (PoP)—a complex combination of custom hardware, machine learning, cryptography, and blockchain technology that Blania says can assign everyone a unique digital identity with complete anonymity.

The Orb is central to this approach. Behind its gleaming surface is a custom optical system that captures high-definition iris scans. To sign up for Worldcoin, enrollees download the company’s app onto their smartphones, where it creates a pair of linked cryptographic keys: a shareable public key and a private key that remains hidden on the user’s device. The public key is used to generate a QR code that the Orb reads before scanning users’ irises. The company says it has invested considerable effort into making Orbs resistant to spoofing sign-ups with modified or fake irises.

The scan is then converted into a string of numbers known as a hash via a one-way function, which makes it nearly impossible to re-create the image even if the hash is compromised. The Orb sends the iris hash and a hash of the user’s public key to Worldcoin’s servers in a signed message. The system checks the iris hash against a database to see if the person has signed up before, and if not, it’s added to the list. The public-key hash is added to a registry on the company’s blockchain.

The process for claiming the user’s free Worldcoins relies on a cryptographic technique known as a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP), which lets a user prove knowledge of a secret without revealing it. The app’s wallet uses an open-source protocol to generate a ZKP showing that the holder’s private key is linked to a public-key hash on the blockchain, without revealing which one. That way, Worldcoin won’t know which public key is associated with which wallet address. Once this linkage is verified by the company’s servers, the tokens are sent to the wallet. The ZKP also includes a string of numbers unique to each user called a nullifier, which shows if they’ve tried to claim their coins before without revealing their identity.

It didn’t take long for Worldcoin to realize that its identity system could have broader applications. According to Blania, the first to spot the potential was Chris Dixon, a partner at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, which led the first investment round in Worldcoin. Blania says that about seven months after the team started work on the project, he told them, “This is super interesting tech, but I think you don’t understand what a big deal it actually is.”

On today’s Internet, most activities flow through centralized platforms like Amazon, Facebook, and PayPal. Blockchain technology could theory remove these middlemen, instead using a decentralized networks of volunteers to regulate such functions as online payments, social media, ride-sharing platforms, and many other types of services—a vision for the future of the Internet dubbed Web3.

Worldcoin’s biggest challenge may not be the functionality of its technology, but questions of trust.

But decentralization also enables new kinds of manipulation, including sybil attacks, named after the 1973 book Sybil, about a woman with multiple personalities. The anonymity of the Internet means it’s easy to create multiple identities that let attackers gain disproportionate influence over decentralized networks. That’s why cryptocurrencies today require members to carry out complex mathematical puzzles or stake large chunks of their money if they want to contribute to core activities like verifying transactions. But that means control of these networks often boils down to how many high-powered computer chips you can afford or how much crypto you hold.

A method to ensure that every member of a network has just one identity could solve the sybil problem in a much more equitable way. And a unique digital ID could have applications beyond Web3, says Tiago Sada, head of product at Worldcoin, such as preventing bot armies on social media, replacing credit-card or government-ID verification to access online services, or even facilitating democratic governance over the Web. Toward the end of last year, Sada says, Worldcoin started work on a new product called World ID—a software-development kit that lets third parties accept ZKPs of “unique humanness” from Worldcoin users.

“A widely adopted PoP changes the nature of the Internet completely,” says Sada. “Once you have sybil resistance, this idea of a unique person [on a blockchain], then it just gives you an order of magnitude more things you can do.”

Despite the startup’s growing focus on World ID, Blania insists its ambitions for the Worldcoin cryptocurrency haven’t diminished. “There is no token that has more than 100 million users,” he says. Worldcoin could have billions. “And really no one knows what the explosion of innovation will be if that actually happens.”

But the coin has yet to be released—those who sign up get an IOU, not actual cryptocurrency—and the company has released few details on how it will work. “They haven’t shared anything regarding what their currency model or their economic model is going to be,” says Anna Stone, who leads commercial strategy for a nonprofit called Good Dollar. “It’s just not yet clear how individual users will benefit.”

Good Dollar distributes small amounts of its own cryptocurrency to anyone who signs up, as a form of UBI. Stone says the project has focused on creating a sustainable stream of UBI for claimants, while Worldcoin seems to be committing far more resources to developing its PoP protocol than the currency itself. “Offering people free crypto is a powerful lead-generation tactic,” she says. “But getting people into your system and getting people using your currency as a currency are two quite different challenges.”

“It’s really hard to revoke and reissue your iris.” – Jon Callas

Leading UBI proponent Karl Widerquist, a professor of philosophy at Georgetown University–Qatar, says he’s skeptical of the potential of cryptocurrencies for boosting financial inclusion or enabling UBI. He says their inherently volatile prices make them unsuitable as currency. But Worldcoin’s one-time distribution seems even less likely to succeed, he says, because most people around the world are so poor that they spend everything they have right away. “The majority of people in the world are going to have none of this currency very quickly.”

The company’s vision for Worldcoin has also shifted as the importance of World ID has grown. While the company can’t dictate what the token will be used for, Sven Seuken, Worldcoin’s head of economics, says it is now positioning the coin as a governance token that gives users a stake in a blockchain-based type of entity called a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO). The company has ambitions to slowly transfer governance of its protocol to a DAO that’s controlled by users, with voting rights linked to their Worldcoin holdings. Tokens would act less as a payment method and more like shares in a company that manages the World ID platform.

This pivot wasn’t reflected in the pitch at the college in Bangalore, where enrollees were sold on the potential of a fast, cheap way to transfer money around the world. Seuken admits the company needs to update its public communications around the benefits of signing up, but he says explaining World ID’s value at this stage of adoption is challenging. “Convincing users initially to sign up by pitching World ID, this would be a really hard sell,” he says.

Informed consent is important, though, says Jon Callas, director of public-interest technology at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It’s problematic, he says, if users don’t realize they’re signing up for a global identity system, especially one that involves biometrics, which are a uniquely sensitive form of authentication. “It’s really hard to revoke and reissue your iris,” says Callas.

While ZKPs provide strong mathematical guarantees of privacy, implementation mistakes can leave gaps that attackers can exploit, says Martin Albrecht, a professor of information security at Royal Holloway, University of London. In 2020, researchers bypassed ZKPs that had been used to anonymize transactions in the privacy-focused cryptocurrency Zcash by exploiting their knowledge that the time taken to generate a proof correlated to the content of transaction data (specifically, the transaction amount).

Worldcoin’s head of blockchain, Remco Bloemen, says that even if the company’s ZKPs were cracked, there wouldn’t be a leak of biometric information, as the ZPKs aren’t connected to users’ iris hashes and are based only on their private keys. But Albrecht says revealing a user’s private key is still a significant problem as it would let you impersonate them. “Once you know someone’s private key, it’s game over,” he says.

Glen Weyl, an economist at Microsoft Research, says that worries about Worldcoin’s threats to privacy are overblown, given that the biometrics aren’t linked to anything. But Worldcoin’s stringent privacy protections have introduced a critical weakness, he adds. Because biometric authentication is a one-time process, there is no ongoing link between users and their World IDs. “You’ve just found a way to generate a key, and that key can be sold or disposed of in any way people want,” he says. “They have no framework, in any sense, for making sure these wallets are tied to the people who received them, other than their trust relationship with the people that they’ve hired to do the recruiting.”

Without an ongoing link between World ID and the underlying biometrics, it’s impossible to audit the registry of users, says Santiago Siri, board member of a competing digital identity system called Proof of Humanity (PoH). That’s why PoH has built its registry of unique humans by getting people to upload videos of themselves that others can challenge if the videos seem fake. Siri concedes that the approach is hard to scale and has significant privacy challenges, but he says the ability to audit a system is critical for its trustworthiness. “How can I verify that of those 750,000 [Worldcoin] identities, 700,000 are not fake, or controlled by Andreessen Horowitz?” he says. “No one will be able to verify that, not even the Worldcoin people.”

It’s also questionable how useful the concept of “unique humanness” really is outside of niche cryptocentric applications, says Kaliya Young, an identity researcher and activist. Identity plays a broader role in everyday life, she says: “I care what your university degrees are, where you were born, how much money you make, all sorts of attributes that PoP doesn’t solve for.”

Worldcoin’s biggest challenge may not be the functionality of its technology but questions of trust. The central goal of blockchains is to avoid relying on centralized authorities, but by using complex, custom hardware to recruit users, the company is setting itself up as a powerful arbiter of digital identity. “Worldcoin posits that everyone in the world should have their eyeball scanned by them and they should be the decider of who’s a unique human,” says Young. “Please explain to me how that’s not ultracentralized.”

What’s more, Microsoft’s Weyl says, the company’s reliance on the “creepy all-seeing eye” of the Orb may create problematic associations. According to Weyl, projects like Worldcoin may give people “a sense of a dystopian future” rather than one that is “hopeful and inclusive.”

In the end, the success of Worldcoin’s ambitious 2023 goals may boil down to a question of narrative. The company is peddling a message of financial inclusion and wealth distribution while critics raise concerns around privacy and transparency. It remains to be seen whether the world will truly buy into Worldcoin.

Edd Gent is a freelance science and technology writer based in Bangalore, India. His writing focuses on emerging technologies across computing, engineering, energy and bioscience. He's on Twitter at @EddytheGent and email at edd dot gent at outlook dot com. His PGP fingerprint is ABB8 6BB3 3E69 C4A7 EC91 611B 5C12 193D 5DFC C01B. His public key is here. DM for Signal info.

The Commodordion is played just like a traditional instrument

Like a traditional accordion, the Commodordion can be played by squeezing the bellows and pressing keys, but in addition, it has sequencer features.

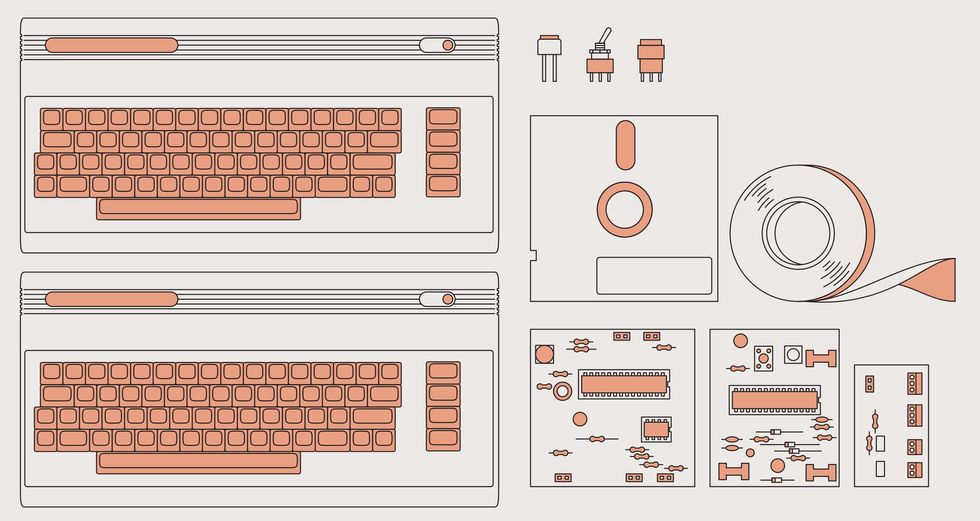

Accordions come in many shapes. Some have a little piano keyboard while others have a grid of black and white buttons set roughly in the shape of a parallelogram. I’ve been fascinated by this “chromatic-button” layout for a long time. I realized that the buttons are staggered just like the keys on a typewriter, and this insight somehow turned into a blurry vision of an accordion built from a pair of 1980s home computers—these machines typically sported a built-in keyboard in a case big enough to form the two ends of an accordion. The idea was intriguing—but would it really work?

I’m an experienced Commodore 64 programmer, so it was an obvious choice for me to use that machine for the accordion ends. As a retrocomputing enthusiast, I wanted to use vintage C64s with minimal modifications rather than, say, gutting the computer cases and putting modern equipment inside.

As for what would go between the ends, accordion bellows are a set of semi-rigid sheets, typically rectangular with an opening in the middle. The sheets are attached to each other alternating between the inner and outer edges. Another flash of insight: The bellows could be made from a stack of 5.25-inch floppy disks.

Now I had several compelling ideas that seemed to work together. I secured a large quantity of bad floppies from a fellow C64 enthusiast. And then, armed with everything I needed and eager to start, I was promptly distracted by other projects.

Some of these projects involved ways of playing music live on C64 computers. The idea to model a musical keyboard layout after the chromatic-button accordion became a standalone C64 program released to the public called Qwertuoso.

That could well have been the end of it, but I had all these disks on my hands, so I decided to go ahead and try to craft a bellows after all. The body of a floppy disk is made from a folded sheet of plastic, which I unfolded to form the bellow’s segments. But I had underestimated the problem of air leakage. While the floppy-disk material is airtight, the seams aren’t. In the end I had to patch the whole thing up with multiple layers of tape to get the air to stay inside.

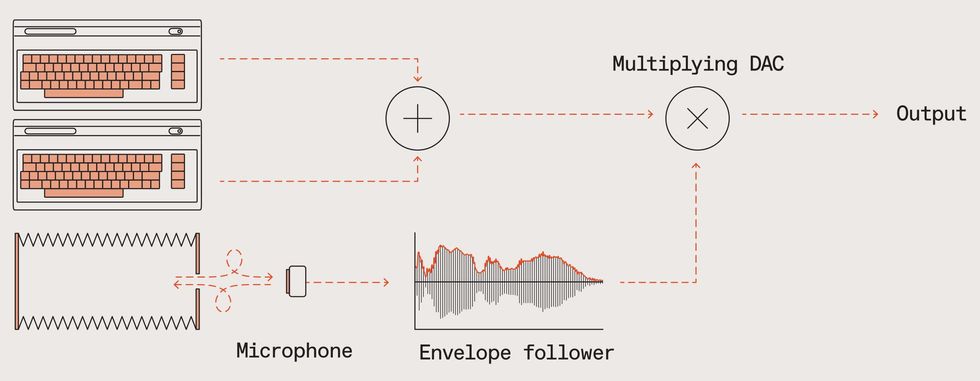

A real accordion uses the bellows to push air over reeds to make them vibrate. How fast the bellows is pumped determines the accordion’s loudness. So I needed a way to sense how fast air was being squeezed out of my floppy-disk bellows as I played.

This was trickier than I had anticipated. I went through several failed designs including one inspired by the “hot wire” sensors used in fuel injection systems. Then one day, I was watching a video and I realized that a person in the video was shouting in order to overcome noise caused by wind hitting his microphone. That was the breakthrough I needed! The solution turned out to be a small microphone, mounted at an angle just outside a small hole in the bellows.

Air flowing into or out of the hole passes over the microphone, and the resulting turbulence turns into audio noise. The intensity of the noise is measured, in my case by an ATmega8 microcontroller, and is used to determine the output volume of the instrument.

The bellows is attached to a simple frame built from wood and acrylic, which also holds the C64s as well as three boards with supporting electronics. One of these is a power hub that takes in 5 and 12 volts of DC electricity from two household-power adapters and distributes it to the various components. For ergonomic reasons, rather than using the normal socket on the C64s right-hand sides, I fed power into the C64s by wires passed through the case and directly soldered to the motherboards.

A second board emulates Commodore’s datasette tape recorder. This stores the Qwertuoso program. Once the C64s are turned on, a keyboard shortcut built into the original OS directs the computer to load from tape. The final board contains the microcontroller monitoring the bellows’ microphone and mixers that combine the analog sound generated by each C64s 6581 SID audio chip and adjusts the volume as per the bellows air sensor. The audio signal is then passed to an external amplified loudspeaker to produce sound.

In order to reach the keys on the left-hand side when the bellows is extended, my hand needs to bend quite far around the edge of what I dubbed the Commodordion. This puts a lot of strain on the hand, wrist, and arm. Partly for this reason, I developed a sequencer for the left-hand-side machine, whereby I can program a simple beat or pattern and have it repeat automatically. With this, I only have to press keys on the left-hand side occasionally, to switch chords.

The Commodordionwww.youtube.com

As a musician, I have to take ergonomics seriously. When you learn to play a piece of music, you practice the same motions over and over for hours. If those motions cause strain you can easily ruin your body. So, unfortunately, I have to restrict myself to playing the Commodordion only occasionally, and only play very simple parts with the left hand.

On the other hand, the right-hand side feels absolutely fine, and that’s very encouraging: I’ll use that as a starting point as I continue to explore the design space of instruments made from old computers. In that light, the Commodordion wasn’t the final goal after all, but an important piece of scaffolding for my next creative endeavor.

In this presentation we will build the case for component-based requirements management

This is a sponsored article brought to you by 321 Gang.

To fully support Requirements Management (RM) best practices, a tool needs to support traceability, versioning, reuse, and Product Line Engineering (PLE). This is especially true when designing large complex systems or systems that follow standards and regulations. Most modern requirement tools do a decent job of capturing requirements and related metadata. Some tools also support rudimentary mechanisms for baselining and traceability capabilities (“linking” requirements). The earlier versions of IBM DOORS Next supported a rich configurable traceability and even a rudimentary form of reuse. DOORS Next became a complete solution for managing requirements a few years ago when IBM invented and implemented Global Configuration Management (GCM) as part of its Engineering Lifecycle Management (ELM, formerly known as Collaborative Lifecycle Management or simply CLM) suite of integrated tools. On the surface, it seems that GCM just provides versioning capability, but it is so much more than that. GCM arms product/system development organizations with support for advanced requirement reuse, traceability that supports versioning, release management and variant management. It is also possible to manage collections of related Application Lifecycle Management (ALM) and Systems Engineering artifacts in a single configuration.

Global Configuration Management – The Game Changer for Requirements Management

In this presentation we will build the case for component-based requirements management, illustrate Global Configuration Management concepts, and focus on various Component Usage Patterns within the context of GCM 7.0.2 and IBM’s Engineering Lifecycle (ELM) suite of tools.

Watch on-demand webinar now →

Before GCM, Project Areas were the only containers available for organizing data. Project Areas could support only one stream of development. Enabling application local Configuration Management (CM) and GCM allows for the use of Components. Components are contained within Project Areas and provide more granular containers for organizing artifacts and new configuration management constructs; streams, baselines, and change sets at the local and global levels. Components can be used to organize requirements either functionally, logically, physically, or using some combination of the three. A stream identifies the latest version of a modifiable configuration of every artifact housed in a component. The stream automatically updates the configuration as new versions of artifacts are created in the context of the stream. The multiple stream capability in components equips teams the tools needed to seamlessly manage multiple releases or variants within a single component.

GCM arms product/system development organizations with support for advanced requirement reuse, traceability that supports versioning, release management, and variant management.

Prior to GCM support, the associations between Project Areas would enable traceability between single version of ALM artifacts. With GCM, virtual networks of components can be constructed allowing for traceability between artifacts across components – between requirements components and between artifacts across other ALM domains (software, change management, testing, modeling, product parts, etc.).

321 Gang has defined common usage patterns for working with components and their streams. These patterns include Variant Development, Parallel Release Management, Simple Single Stream Development, and others. The GCM capability for virtual networks and the use of some of these patterns provide a foundation to support PLE.

The 321 Gang has put together a short webinar also titled Global Configuration Management: A Game Changer for Requirements Management, that expands on the topics discussed here. During the webinar we build a case for component-based requirements management, illustrate Global Configuration Management concepts, and introduce common GCM usage patterns using ELM suite of tools. Watch this on-demand webinar now.