IEEE websites place cookies on your device to give you the best user experience. By using our websites, you agree to the placement of these cookies. To learn more, read our Privacy Policy.

Many challenges still lie ahead for postquantum cryptography

Future quantum computers may rapidly break modern cryptography. Now researchers find that a promising algorithm designed to protect computers from these advanced attacks could get broken in just 4 minutes. And the catch is that 4-minute time stamp was not achieved by a cutting-edge machine but by a regular 10-year-old desktop computer. This latest, surprising defeat highlights the many hurdles postquantum cryptography will need to clear before adoption, researchers say.

In theory, quantum computers can quickly solve problems it might take classical computers untold eons to solve. For example, much of modern cryptography relies on the extreme difficulty that classical computers face when it comes to mathematical problems such as factoring huge numbers. However, quantum computers can in principle run algorithms that can rapidly crack such encryption.

To stay ahead of this quantum threat, cryptographers around the world have spent the past two decades designing postquantum cryptography (PQC) algorithms. These are based on new mathematical problems that both quantum and classical computers find difficult to solve.

“What is most surprising is that the attack seemingly came out of nowhere.”

—Jonathan Katz, University of Maryland at College Park

For years, researchers at organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have been investigating which PQC algorithms should become the new standards the world should adopt. NIST announced it was seeking candidate PQC algorithms in 2016, and received 82 submissions in 2017. In July, after three rounds of review, NIST announced four algorithms that would become standards, and four more would enter another round of review as possible additional contenders.

Now a new study has revealed a way to completely break one of these contenders under review, known as SIKE, which Microsoft, Amazon, Cloudflare, and others have investigated. “The attack came from out of the blue, and was a silver bullet,” says cryptographer Christopher Peikert at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, who did not take part in this new work.

SIKE (Supersingular Isogeny Key Encapsulation) is a family of PQC algorithms involving elliptic curves. “Elliptic curves have long been studied in mathematics,” says mathematician Dustin Moody at NIST, who did not take part in this new work. “They are described by an equation looking like y2 = x3 + Ax + B, where A and B are numbers. So for example, an elliptic curve could be y2 = x3 + 3x + 2.”

In 1985, “mathematicians figured out a way to make cryptosystems involving elliptic curves, and these systems have been widely deployed,” Moody says. “However, these elliptic curve cryptosystems turn out to be vulnerable to attacks from a quantum computer.”

Around 2010, researchers found a new way to use elliptic curves in cryptography. “It was believed that this new idea wasn’t susceptible to attacks from quantum computers,” Moody says.

This new approach is based on how two points can be added on an elliptic curve to get another point on the elliptic curve, Moody says. An “isogeny” is a map from one elliptic curve to another elliptic curve that preserves this addition law.

“If you make this map complex enough, the conjectured hard problem, which allows encryption of data, is that given two elliptic curves, it’s hard to find an isogeny between them,” says study coauthor Thomas Decru, a mathematical cryptographer at KU Leuven in Belgium.

SIKE is a form of isogeny-based cryptography based on the Supersingular Isogeny Diffie-Hellman (SIDH) key exchange protocol. “SIDH/SIKE was one of the first practical isogeny-based cryptographic protocols,” Decru says.

However, one of SIKE’s vulnerabilities was that in order for it to work, it needed to provide extra information to the public known as auxiliary torsion points. “Attackers have tried to exploit this extra information for a while, but had not been successful in using it to break SIKE,” Moody says. “However, this new paper found a way to do it, using some pretty advanced mathematics.”

To explain this new attack, Decru says that although elliptic curves are one-dimensional objects, in mathematics elliptic curves can be visualized as objects of two dimensions or any other number of dimensions. One can also create isogenies between these generalized objects.

“People were naturally concerned that there might still be major attacks to be discovered, and they were right.”

—Steven Galbraith, University of Auckland

By applying a 25-year-old theorem, the new attack uses the extra information that SIKE makes public to construct an isogeny in two dimensions. This isogeny can then reconstruct the secret key that SIKE uses to encrypt a message. Decru and study senior author Wouter Castryck detailed their findings on 5 August in the Cryptology ePrint Archive.

“To me what is most surprising is that the attack seemingly came out of nowhere,” says cryptographer Jonathan Katz at the University of Maryland at College Park, who did not take part in this new work. “There were very few prior results showing any weaknesses in SIKE, and then suddenly this result appeared with a completely devastating attack—namely, it finds the entire secret key, and does so relatively quickly without any quantum computation.”

Using an algorithm based on this new attack, the researchers found that a 10-year-old Intel desktop took 4 minutes to find a secret key secured by SIKE.

“Usually, when a proposed cryptosystem gets seriously attacked, this happens relatively soon after the system is proposed, or begins to attract attention, or in a progression of research results over time, or yields not a total break but significant weakening of the system. In this instance we saw none of that,” Peikert says. “Attacks on SIDH/SIKE went from essentially no progress for 11 to 12 years, since SIDH was first proposed, to a total break.”

Although researchers had tested SIKE for more than a decade, “one of the reasons why SIKE was not selected for standardization is that there was concern that it is too new and has not been studied enough,” says mathematician Steven Galbraith at the University of Auckland, in New Zealand, who did not take part in this new work. “People were naturally concerned that there might still be major attacks to be discovered, and they were right.”

One reason SIKE’s vulnerability was not detected until now was because the new attack “applies very advanced mathematics—I can’t think of another situation where an attack has used such deep mathematics compared with the system being broken,” says Galbraith. Katz agrees, saying, “I suspect that fewer than 50 people in the world understand both the underlying mathematics and the necessary cryptography.”

Moreover, isogenies “are notoriously ‘difficult,’ both from an implementation and a theoretical perspective,” says cryptographer David Joseph at the PQC startup Sandbox AQ in Palo Alto, Calif., who did not take part in this new work. “This makes it more likely that fundamental flaws can persist undetected so late in the competition.”

“We proposed a system, which everyone agrees seemed like a good idea at the time, and after subsequent analysis someone is able to find a break. It is unusual that it took 10 years, but otherwise nothing to see here.”

—David Jao, University of Waterloo

Furthermore, “it should be noted that with many more algorithms in earlier rounds, the cryptanalysis was spread much more thinly, whereas for the past couple of years researchers have been able to concentrate on a smaller batch of algorithms,” Joseph says.

SIKE co-inventor David Jao, a professor at the University of Waterloo, in Canada, says, “I think the new result is magnificent work and I give the authors my highest praise.” At first, “I felt sad that SIKE had been invalidated, because it is such a mathematically elegant scheme, but the new findings simply reflect how science works,” he says. “We proposed a system, which everyone agrees seemed like a good idea at the time, and after subsequent analysis someone is able to find a break. It is unusual that it took 10 years, but otherwise nothing to see here except the ordinary course of progress.“

In addition, “it’s far better for SIKE to be broken now than in some hypothetical alternative world where SIKE becomes widely deployed and everyone comes to rely on it before it gets broken,” Jao says.

SIKE is the second NIST PQC candidate to get broken this year. In February, cryptographer Ward Beullens at IBM Research, in Zurich, revealed he could break third-round candidate Rainbow in a weekend on a laptop. “So this shows that all the PQC schemes still require further study,” Katz says.

Still, these new findings break SIKE but not other isogeny-based cryptography systems, such as CSIDH or SQIsign, Moody notes. “People from the outside may think isogeny-based cryptography is dead now, but this is far from true,” Decru says. “There’s still much to research, if you ask me.”

In addition, this new work also may not reflect one way or the other on NIST’s PQC research. SIKE was the only isogeny-based cryptosystem of the 82 submissions that NIST received. Similarly, Rainbow was the only multivariate algorithm among those submissions, Decru says.

“We have no absolute guarantee of security for any cryptosystem. The best we can say is that after a lot of study by a lot of smart people, nobody has found any cracks.”

—Dustin Moody, NIST

The other designs that NIST is adopting as standards or have made it to NIST’s fourth round “are based on mathematical ideas that have a longer track record of study and analysis by cryptographers,” Galbraith says. “This does not guarantee they are secure, but it just means they have withstood attacks for a longer time.”

Moody agrees, noting “it is always the case that some amazing breakthrough result could be discovered which breaks a cryptosystem. We have no absolute guarantee of security for any cryptosystem. The best we can say is that after a lot of study by a lot of smart people, nobody has found any cracks in the cryptosystem.”

Still, “our process was designed to allow for attacks and breaks,” Moody says. “We’ve seen them in each of the evaluation rounds. It’s the only way to gain confidence in the security.” Galbraith agrees, noting that such research “is the process working.”

Nevertheless, “I feel like the combination of Rainbow and SIKE falling will make more people seriously think about requiring a back-up plan for any winner that emerges from the NIST postquantum standardization process,” Decru says. “Relying on just one mathematical concept or scheme may be too risky. This is something NIST themselves thinks as well—their main scheme will most likely be lattice-based, but they want a nonlattice backup.”

Decru notes that other researchers are already developing new versions of SIDH/SIKE they suggest may thwart this new attack. “I expect more such results to follow, where people try to patch SIDH/SIKE, as well as improvements on our attack,” Decru says.

All in all, the fact that the starting point of this new attack was a theorem “totally unrelated to cryptography” shows “the importance of fundamental research in pure mathematics in order to understand cryptosystems,” Galbraith says.

Decru agrees, noting that “in mathematics, not everything is applicable right away. Hell, there are things that will almost surely never be applicable to any real-life situation. But that doesn’t mean we should not allow research to steer in these more obscure topics from time to time.”

Charles Q. Choi is a science reporter who contributes regularly to IEEE Spectrum. He has written for Scientific American, The New York Times, Wired, and Science, among others.

A cautionary tale of NFTs, Ethereum, and cryptocurrency security

On 4 September 2018, someone known only as Rabono bought an angry cartoon cat named Dragon for 600 ether—an amount of Ethereum cryptocurrency worth about US $170,000 at the time, or $745,000 at the cryptocurrency’s value in July 2022.

It was by far the highest transaction yet for a nonfungible token (NFT), the then-new concept of a unique digital asset. And it was a headline-grabbing opportunity for CryptoKitties, the world’s first blockchain gaming hit. But the sky-high transaction obscured a more difficult truth: CryptoKitties was dying, and it had been for some time.

Dragon was never resold—a strange fate for one of the most historically relevant NFTs ever. Newer NFTs such as “The Merge,” a piece of digital art that sold for the equivalent of $92 million, left Dragon behind as the NFT market surged to record sales, totaling roughly $18 billion in 2021. Has the world simply moved on to newer blockchain projects? Or is this the fate that awaits all NFTs?

To understand the slow death of CryptoKitties, you have to start at the beginning. Blockchain technology arguably began with a 1982 paper by the computer scientist David Chaum, but it reached mainstream attention with the success of Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency created by the anonymous person or persons known as Satoshi Nakamoto. At its core, a blockchain is a simple ledger of transactions placed one after another—not unlike a very long Excel spreadsheet.

The complexity comes in how blockchains keep the ledger stable and secure without a central authority; the details of how that’s done vary among blockchains. Bitcoin, though popular as an asset and useful for money-like transactions, has limited support for doing anything else. Newer alternatives, such as Ethereum, gained popularity because they allow for complex “smart contracts”—executable code stored in the blockchain.

“Before CryptoKitties, if you were to say ‘blockchain,’ everyone would have assumed you’re talking about cryptocurrency”—Bryce Bladon

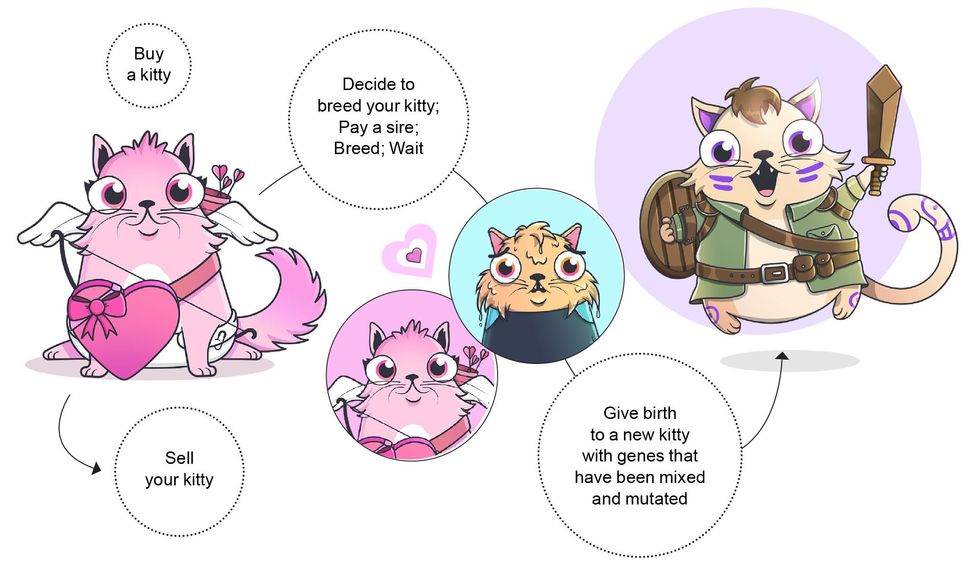

CryptoKitties was among the first projects to harness smart contracts by attaching code to data constructs called tokens, on the Ethereum blockchain. Each chunk of the game’s code (which it refers to as a “gene”) describes the attributes of a digital cat. Players buy, collect, sell, and even breed new felines. Just like individual Ethereum tokens and bitcoins, the cat’s code also ensures that the token representing each cat is unique, which is where the nonfungible token, or NFT, comes in. A fungible good is, by definition, one that can be replaced by an identical item—one bitcoin is as good as any other bitcoin. An NFT, by contrast, has unique code that applies to no other NFT.

There’s one final piece of the blockchain puzzle you need to understand: “gas.” Some blockchains, including Ethereum, charge a fee for the computational work the network must do to verify a transaction. This creates an obstacle to overworking the blockchain’s network. High demand means high fees, encouraging users to think twice before making a transaction. The resulting reduction in demand protects the network from being overloaded and transaction times from becoming excessively long. But it can be a weakness when an NFT game goes viral.

Launched on 28 November 2017 after a five-day closed beta, CryptoKitties skyrocketed in popularity on an alluring tagline: the world’s first Ethereum game.

“As soon as it launched, it pretty much immediately went viral,” says Bryce Bladon, a founding member of the team that created CryptoKitties. “That was an incredibly bewildering time.”

Sales volume surged from just 1,500 nonfungible felines on launch day to more than 52,000 on 10 December 2017, according to nonfungible.com, with many CryptoKitties selling for valuations in the hundreds or thousands of dollars. The value of the game’s algorithmically generated cats led to coverage in hundreds of publications.

Each CryptoKitty is a token, a set of data on the Ethereum blockchain. Unlike the cryptocurrencies Ethereum and Bitcoin, these tokens are nonfungible; that is, they are not interchangeable.

Dapper Labs

What’s more, the game arguably drove the success of Ethereum, the blockchain used by the game. Ethereum took off like a rocket in tandem with the release of CryptoKitties, climbing from just under $300 per token at the beginning of November 2017 to just over $1,360 in January 2018.

Ethereum’s rise continued with the launch of dozens of new blockchain games based on the cryptocurrency through late 2017 and 2018. Ethermon, Ethercraft, Ether Goo, CryptoCountries, CryptoCelebrities, and CryptoCities are among the better-known examples. Some arrived within weeks of CryptoKitties.

This was the break fans of Ethereum were waiting for. Yet, in what would prove an ominous sign for the health of blockchain gaming, CryptoKitties stumbled as Ethereum dashed higher.

Daily sales peaked in early December 2017, then slid into January and, by March, averaged less than 3,000. The value of the NFTs themselves declined more slowly, a sign the game had a base of dedicated fans like Rabono, who bought Dragon well after the game’s peak. Their activity set records for the value of NFTs through 2018. This kept the game in the news but failed to lure new players.

Today, CryptoKitties is lucky to break 100 sales a day, and the total value is often less than $10,000. Large transactions, like the sale of Founder Cat #71 for 60 ether (roughly $170,000) on 30 April 2022, do still occur—but only once every few months. Most nonfungible fur-babies sell for tiny fractions of 1 ether, worth just tens of dollars in July 2022.

CryptoKitties’ plunge into obscurity is unlikely to reverse.Dapper Labs, which owns CryptoKitties, has moved on to projects such as NBA Top Shot, a platform that lets basketball fans purchase NFT “moments”—essentially video clips—from NBA games. Dapper Labs did not respond to requests for an interview about CryptoKitties. Bladon left Dapper in 2019.

One clue to the game’s demise can be found in the last post on the game’s blog (4 June 2021), which celebrates the breeding of the 2 millionth CryptoKitty. Breeding, a core mechanic of the game, lets owners pair their existing NFTs to create algorithmically generated offspring. This gave the NFTs inherent value in the game’s ecosystem. Each NFT was able to generate more NFTs, which players could then resell for profit. But this game mechanism also saturated the market. Xiaofan Liu, an assistant professor in the department of media and communication at City University of Hong Kong who coauthored a paper on CryptoKitties’ rise and fall, sees this as a flaw the game could never overcome.

“The price of a kitty depends first on rarity, and that depends on the gene side. And the second dimension is just how many kitties are on the market,” Liu says. “With more people came more kitties.”

More players meant more demand, but it also meant more opportunities to create supply through breeding new cats. This quickly diluted the rarity of each NFT.

Bladon agrees with that assessment of the breeding mechanism. “I think the criticism is valid,” he says, explaining that it was meant to provide a sense of discovery and excitement. He also hoped it would encourage players to hold on to NFTs instead of immediately selling, as breeding, in theory, provided lasting value.

The sheer volume of CryptoKitties caused another, more immediate problem: It functionally broke the Ethereum blockchain, which is the world’s second most valuable cryptocurrency by market capitalization (after Bitcoin). As explained earlier, Ethereum uses a fee called gas to price the cost of transactions. Any spike in transactions—buying, siring, and so on—will cause a spike in gas fees, and that’s exactly what happened when CryptoKitties went to the moon.

“Anything that was emblematic of CryptoKitties’ success was aped. Anything that wasn’t immediately visible was mostly ignored.”—Bryce Bladon

“Players who wanted to buy CryptoKitties incurred high gas fees,” Mihai Vicol, market analyst at Newzoo, said in an interview. “Those gas fees were anywhere from $100 to $200 per transaction. You had to pay the price of the CryptoKitty, plus the gas fee. That’s a major issue.”

The high fees weren’t just a problem for CryptoKitties. It was an issue for the entire blockchain. Anyone who wanted to transact in Ethereum, for any reason, had to pay more for gas as the game became more successful.

This dynamic remains a problem for Ethereum today. On 30 April 2022, when Yuga Labs released Otherdeeds—NFTs that promise owners metaverse real estate—it launched Ethereum gas fees into the stratosphere. The average price of gas briefly exceeded the equivalent of $450, up from about $50 the day before.

Although CryptoKitties’ demands on the network subsided as players left, gas will likely be the final nail in the game’s coffin. The median price of a CryptoKitty in the past three months is about 0.04 ether, or $40 to $50, which is often less than the gas required to complete the transaction. Even those who want to casually own and breed inexpensive CryptoKitties for fun can’t do it without spending hundreds of dollars.

The rise and fall of CryptoKitties was dramatic but gave its successors—of which there are hundreds—a chance to learn from its mistakes and move past them. Many have failed to heed the lessons: Modern blockchain gaming hits such as Axie Infinity and BinaryX had a similar initial surge in price and activity followed by a long downward spiral.

“Anything that was emblematic of CryptoKitties’ success was aped. Anything that wasn’t immediately visible was mostly ignored,” says Bladon. And it turns out many of CryptoKitties’ difficulties weren’t visible to the public. “The thing is, the CryptoKitties project did stumble. We had a lot of outages. We had to deal with a lot of people who’d never used blockchain before. We had a bug that leaked tens of thousands of dollars of ether.” Similar problems have plagued more recent NFT projects, often on a much larger scale.

Liu isn’t sure how blockchain games can curb this problem. “The short answer is, I don’t know,” he says. “The long answer is, it’s not just a problem of blockchain games.”

World of Warcraft, for example, has faced rampant inflation for most of the game’s life. This is caused by a constant influx of gold from players and the ever-increasing value of new items introduced by expansions. The continual need for new players and items is linked to another core problem of today’s blockchain games: They’re often too simple.

“I think the biggest problem blockchain games have right now is they’re not fun, and if they’re not fun, people don’t want to invest in the game itself,” says Newzoo’s Vicol. “Everyone who spends money wants to leave the game with more money than they spent.”

The launch of CryptoKitties drove up the value of Ether and the number of transactions on its blockchain. Even as the game's transaction volume plummeted, the number of Ethereum transactions continued to rise, possibly because of the arrival of multiple copycat NFT games.

That perhaps unrealistic wish becomes impossible once the downward spiral begins. Players, feeling no other attachment to the game than growing an investment, quickly flee and don’t return.

Whereas some blockchain games have seemingly ignored the perils of CryptoKitties’ quick growth and long decline, others have learned from the strain it placed on the Ethereum network. Most blockchain games now use a sidechain, a blockchain that exists independently but connects to another, more prominent “parent” blockchain. The chains are connected by a bridge that facilitates the transfer of tokens between each chain. This prevents a rise in fees on the primary blockchain, as all game activity occurs on the sidechain.

Yet even this new strategy comes with problems, because sidechains are proving to be less secure than the parent blockchain. An attack on Ronin, the sidechain used by Axie Infinity, let the hackers get away with the equivalent of $600 million. Polygon, another sidechain often used by blockchain games, had to patch an exploit that put $850 million at risk and pay a bug bounty of $2 million to the hacker who spotted the issue. Players who own NFTs on a sidechain are now warily eyeing its security.

The cryptocurrency wallet that owns the near million dollar kitten Dragon now holds barely 30 dollars’ worth of ether and hasn’t traded in NFTs for years. Wallets are anonymous, so it’s possible the person behind the wallet moved on to another. Still, it’s hard not to see the wallet’s inactivity as a sign that, for Rabono, the fun didn’t last.

Whether blockchain games and NFTs shoot to the moon or fall to zero, Bladon remains proud of what CryptoKitties accomplished and hopeful it nudged the blockchain industry in a more approachable direction.

“Before CryptoKitties, if you were to say ‘blockchain,’ everyone would have assumed you’re talking about cryptocurrency,” says Bladon. “What I’m proudest of is that it was something genuinely novel. There was real technical innovation, and seemingly, a real culture impact.”

This article was corrected on 11 August 2022 to give the correct date of Bryce Bladon's departure from Dapper Labs.