Advertisement

Supported by

critic’s notebook

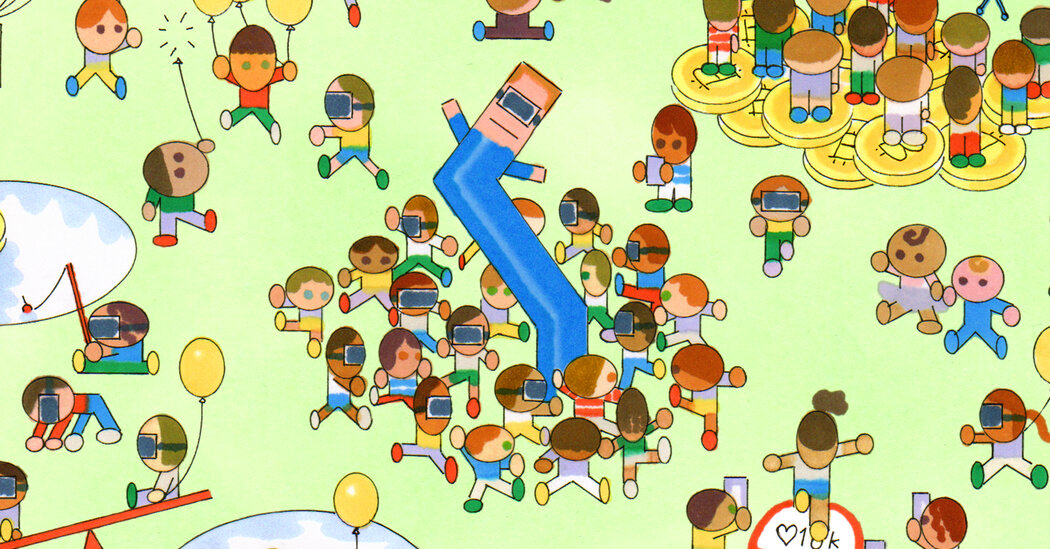

The new frontier of children’s entertainment is internet-native cartoon characters selling nonfungible tokens on social-media apps for tots.

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

When Olympia Ohanian — the daughter of the tennis player Serena Williams and the internet entrepreneur Alexis Ohanian — was an infant, her parents got her a plastic baby doll. Then they got that doll an Instagram account.

Qai Qai, as the doll was named, emerged on the platform in 2018 in a series of enigmatic photographs. Though the doll’s feed resembled crime-scene photography — Qai Qai could be dumped unceremoniously in a sandbox or splayed lifelessly on a lonely stretch of asphalt — it also had a delightfully nostalgic quality. The images embodied the comic dark side of a young child’s obsessional devotion to a beloved object: When a new plaything appears, the object may be ruthlessly discarded. Every photo of Qai Qai’s casual neglect seemed infused with Olympia’s own boundless spirit.

As the doll amassed followers, however, she adapted to the demands of various online platforms. Soon she had mutated into a computer-generated cartoon figure with doe eyes and a curlicue of hair atop her head. This new, seemingly sentient Qai Qai could lip-sync to viral videos like a TikTok star and wave from an F. A. O. Schwarz toy convertible like a mini influencer. Eventually the original Qai Qai doll vanished from social media, replaced instead by a new one styled after the cartoon version and available for purchase on Amazon. Last week, Qai Qai dropped her first NFT collection.

Qai Qai is part of a movement to drag children’s entertainment into the digital future. She was animated by the tech company Invisible Universe, which develops internet-native cartoon-character intellectual property attached to celebrities. (Invisible Universe has also created a long-lost teddy bear character for the TikTok-famous D’Amelio family and a cartoon food influencer dog for Jennifer Aniston.) And Qai Qai’s NFTs — or nonfungible tokens, unique digital assets that have birthed a highly speculative marketplace riddled with gimmickry — were released on Zigazoo, an app for children as young as 3 that bills itself as “the world’s largest social network and NFT platform for kids.”

Does your toddler need an NFT? Zigazoo says yes. The app’s mission is to “empower kids to shape the very landscape and infrastructure of NFTs and Web3,” to help them “express themselves through art and practice essential financial literacy skills” and to allow them to grow into “tomorrow’s digital citizens.” As Rebecca Jennings recently reported in Vox, efforts to usher children into the worlds of cryptocurrency, NFTs and blockchain technology are being pitched as “preparing future workers for lucrative jobs in tech.” Traditional children’s entertainment has long angled at extracting maximum cash from its little consumers (soon Pixar will release a gritty origin film featuring the “Toy Story” character Buzz Lightyear), but the slick language suggesting that kids should spend money to make money feels new. Platforms like Zigazoo are building a hype bubble for children and pitching it as a creative outlet, an educational opportunity, even a civic duty to join in.

Recently I practiced my own essential financial literacy skills by acquiring a set of images of Qai Qai dancing in a tutu. First I had to download Zigazoo, which is a kind of junior TikTok designed to be managed by an adult caregiver. Once you’re inside, the app solicits videos built around anodyne “challenges,” like “Can you sing in another language?,” and not-too-personal questions, like “What are your favorite shoes to wear?” The content feels less important than the design of the app, which, like any grown-up social network, encourages users to amass followers, rack up likes and generally become Zigazoo-famous. In Zigazoo-ese, this might be translated as “practicing essential attention economy skills.”

Many of the app’s users appear charmingly unpolished, posting shaky videos that cut their faces off at their foreheads or chins as they deliver breathless extemporaneous monologues. And yet their dispatches are infused with the language of influencers; a typical video begins with “Hey Zigazoo friends!” and ends with “Like and subscribe!” Along the way there are apologies for not posting recently, promises to post more soon and offers to shout out the user’s most engaged followers in the next post, even if those followers don’t exist. Occasionally this strange and tender feed will be interrupted by an oddly glossy video — like from a big-on-Zigazoo child actor who can execute his challenges while staring meaningfully into the lens and tickling a piano just out of frame. (When I signed up, Zigazoo suggested I follow him, along with an account associated with the “Paw Patrol” movie and a teenage “Ninja Warrior” champion.) Occasionally, adults will appear. Usually they are selling something, like a toy subscription box or a podcast for children.

Common Sense Media, a nonprofit that rates the age appropriateness of media and technology, gives Zigazoo high marks for its lack of images of violence, drugs and “sexy stuff.” There are no comments on the app, only positive-reinforcement mechanisms, and each video is moderated by a human being. But though Common Sense’s review states that consumerism is “not present” on the app, it is everywhere. Every time I opened Zigazoo, I learned that I had earned more “Zigabucks,” the platform’s in-app currency, for dutifully visiting every day. Also, I was constantly prompted to care about Zigazoo’s latest NFT drop: images featuring JJ, the cartoon infant star of CoComelon.

CoComelon is a wildly popular YouTube channel featuring crudely rendered C.G.I. videos and repetitive nursery rhymes, like “Dentist Song” and “Pasta Song.” Though it has no discernible value beyond its ability to hypnotize toddlers for long stretches of time, it has taken over the world; recently the brand partnered with the Saudi government to construct a physical CoComelon village in Riyadh, perhaps as a part of Saudi Arabia’s larger public-relations effort to become known for something other than torturing dissidents. (Let’s call that “practicing essential geopolitical skills.”)

Anyway, children love it: The CoComelon NFTs were sold out before I could snag one, so I waited for the Qai Qai NFTs to drop, watching the countdown clock on the Zigazoo app for my moment to “invest.” Qai Qai’s NFTs were selling for $5.99 to $49.99 a pack, with more cash buying you a higher likelihood of acquiring not just a “common” NFT but a “rare” or “legendary” one, a distinction that went unexplained. (Though every Zigazoo NFT is linked to a unique digital record on the Flow blockchain, the app did not make clear how many of these records it was assigning to each Qai Qai image, which makes it even harder to guess just how worthless it might be in the future.) I selected a “rare” pack of Qai Qai collectibles for $19.99, answered a “Parents only!” multiple-choice multiplication problem to prove I was an adult (although I knew my multiplication tables better when I was a kid), and ultimately was rewarded with four still images of Qai Qai and one “rare” repeating video of Qai Qai executing the “Heel Toe Dance.”

Over the next few days, I was invited to trade my NFTs with other users and participate in NFT-related challenges like “#QaiQaiDrop: What new toy are you hoping to get?” and “CoComelon: Can you show us your favorite pajamas?” Each challenge’s “winner” was rewarded with yet more NFTs. The real challenge in this case appears to be to “express yourself by helping to hype a new tech gimmick to a younger class of consumers.” This concluded my NFT education on Zigazoo.

My Qai Qai NFT is fine. Like the internet’s many dancing babies before her, she is cute, and buying the digital asset also supports a broader project: Serena Williams developed Qai Qai in order to ensure that her daughter’s generation has access to Black dolls, which Williams herself lacked as a child. (I have nothing nice to say about the CoComelon NFTs.) Dolls present endless opportunities for creative play, as exemplified by Qai Qai’s macabre beginnings. Her early Instagram account exemplified the generative power of the internet, the ability to spin up a weird creative project and share it with the world — not because it will help “teach” you how to invest in cryptocurrencies, but just because you feel like it.

In its in-app explainer, “Why should kids have NFTs?,” Zigazoo laments that “so much about the internet is about consumption,” but states that “the future of the internet is what you can create.” Right now, though, it’s about what you can buy using Zigabucks.

Advertisement

Author

Administraroot